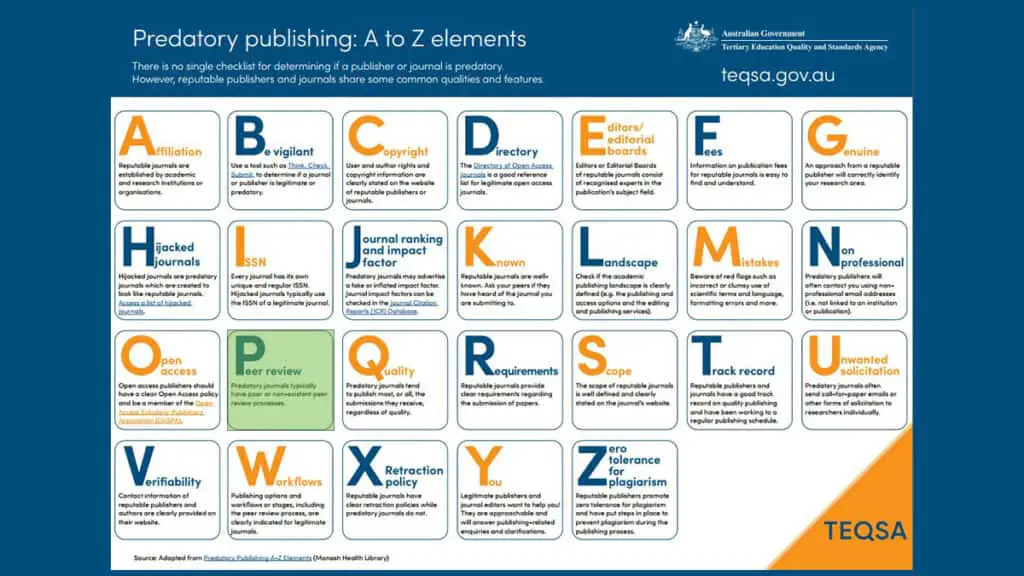

TEQSA (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency) have produced an A-Z of Predatory Publishing, which they tweeted (see figure).

You can also see the infographic on their web site.

We looked at the infographic, in a general sense, in an earlier article, but in this series we are focusing on specific letters, in this case P.

P is for Peer Review

The infographics from TEQSA says:

“Predatory journals typically have poor or non-existent peer review processes.“

We would fully concur with this view, but how do you know if the peer review is poor or non-existent? Here are our thoughts.

Metadata

One of the checks you can is to look at the metadata for a selection of the papers that the journal has published. This data may be on the web page for the particular paper, or the information may be on the paper itself.

If metadata is present (and, of course, it may not be), what are you looking for? In the context of peer review, you need to look at the dates when the paper was submitted, accepted and published (or some variant of those). If they are too close together, it should be (at least) a warning flag.

It is difficult to provide firm guidance but anything less then two months would raise alarm bells. We have seen examples where papers are submitted and accepted in two days. This would be a real concern to us, especially if this was the case across a number of papers and we would probably avoid that journal even if we had carried out no other checks.

Bibliography

A further check that we always do is to look at the bibliography, looking to see when the latest cited paper is dated. It is amazing the number of times you see that the most recently cited paper is at least five years old. This raises a number of issues but from a predatory publishing point of view, it could point to a lack of peer review, as any half decent reviewer should pick up that the related work is not up to date.

An out of date literature review is certainly not a definite indicator of the journal being predatory, but it is an indication of poor review, which is an indicator in itself of the journal being predatory.

English

The level of English can be illuminating. I think that we all feel for those whose native language is not English and we can forgive the odd grammatical error or phrases which grate as you read them. But, as long as the understanding is there, we are happy to let these go by.

The issue comes when the language gets in the way of the meaning and this could be an indicator of the lack of peer review. On our Twitter account we have given some examples of this (see, for example, this tweet and this one).

If the English is so bad it is a strong indicator that there has been no peer review.

Plagiarism

If we have doubts about a paper, with an obvious red flag being when hard to read English suddenly changes to perfect prose, we often run it through a plagiarism checker just to see what turns up.

In one of our studies, we found significant levels of plagiarism in published papers. You can see these examples on our Twitter account. For example, take a look at this tweet and/or this one.

Plagiarism is not a definitive indicator of a predatory journal but it is a warning sign, especially if you cannot find an easy way to report this to the journal (e.g. the is no Editor-in-Chief email, the only journal for the email is a generic gmail address etc.).

Concluding remarks

We’d like to thank TEQSA for creating their infographic. We find it very informative and, more importantly, it gives food for thought.

We hope, in the above article, that we have managed to present our view on how the lack of peer review can be detected which, in turn, provides indicators that the journal is predatory.

Without doubt there are many more way to detect lack of peer review and we would be happy to return to this topic at a later date.