Introduction

It is 15 years since Jeffrey Beall first coined the term ‘predatory publishing’, and after years where the topic appears to have received little attention, several new books have recently been published and we finally seem to be taking this issue seriously – but is it too late?

As one of the authors of these books, Simon Linacre reviews them to see what a better understanding of predatory publishing practices means for scholarly communications.

Over to Simon.

Opening Remarks

Picture the scene: in the Summer of 2021, I have written a short book on predatory journal publishing, mainly because nobody else had. I have done it by spending 119 days straight getting up at 4am or staying up late to fit the writing around work and family, but by the end of the year I have submitted the manuscript to the publisher and now can relax and look forward to the fruits of my labour.

And then I see that in early 2022, someone else is publishing a book called, you guessed it, Predatory Publishing. Damn.

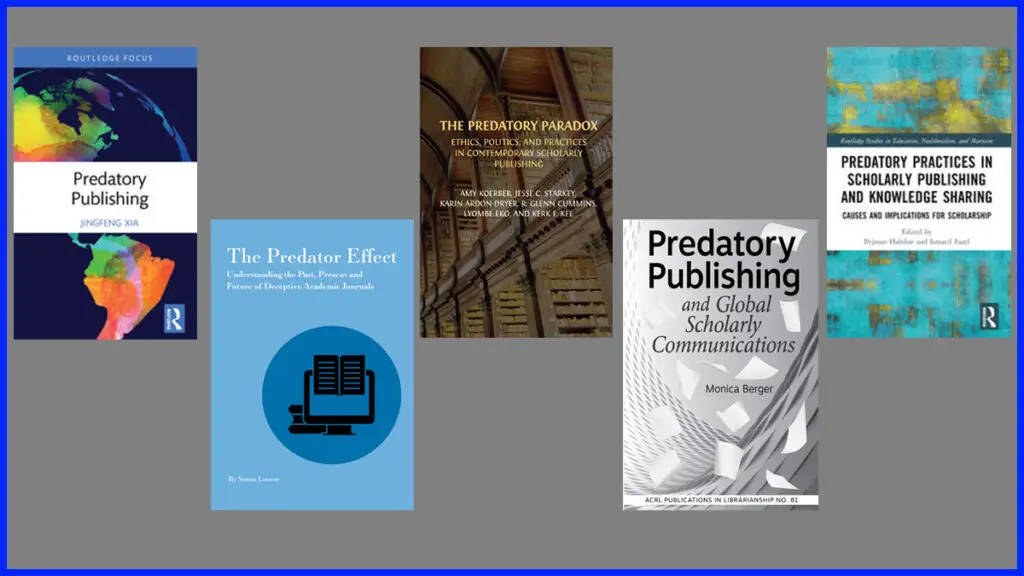

The book was published by independent researcher and former library dean Jingfeng Xia, and was the first of five books in the next two years taking in-depth approaches to the subject of predatory journals. All of them take different approaches, from an edited collection to a focus on pedagogy, but they also share an academic view of the problem, as well as very much agreeing that there is a problem in the first place. This blog is an attempt to review them contextually, as well as extract what they might tell us about how predatory publishing may develop in the next few years.

Predatory Publishing by Jingfeng Xia

Looking at the books chronologically, first off the mark was Predatory Publishing (2022) by Jingfeng Xia. Setting aside my own disappointment at not being the first to publish, it was heartening to see a book like this published by a recognised authority by a major publisher like Routledge. Xia takes a broad approach, looking at predatory conferences and journal hijackings as well as other examples of predatory behaviour. Xia stated he wanted to provide a reference point for academics, and the book achieves this in spades. For example, the sections on responsibility lying with other stakeholders other than the predatory publishers themselves is very well said, and the explanation of fake indices – made to look like Web of Science or Scopus – is extremely valuable.

The Predator Effect: Understanding the Past, Present and Future of Deceptive Academic Journals by Simon Linacre

The focus on equipping authors so that they didn’t fall prey to predators was also one of my own aims for my book, The Predator Effect (2022). However, I also wanted to offer some context as to why predatory journals started to appear from the 2000s onwards, and also bust some myths that had developed. Specifically, the erroneous thinking that open access was somehow to blame for predatory journals, or necessarily shared some of their traits (spoiler alert: they don’t), as well as pleading gently for researchers to avoid Beall’s Lists at all costs. This was not to denigrate Beall himself or the role he played in highlighting the problems of predatory publishing practices, which was absolutely crucial, but to simply highlight that the lists as they exist currently on the internet are at best way out of date and inherently subjective, and at worst bastardised and exhibit the very same characteristics of the predatory journals they purport to identify.

The Predatory Paradox: Ethics, Politics, and Practices in Contemporary Scholarly Publishing by Amy Koerber et al.

Unsurprisingly, Beall looms large over books published on predatory publishing, despite the fact they were all published at least five years after he took down his website in 2017. Each one has a slightly different take, with the next book to come out on the topic explaining in various ways how he had influenced more open evaluation of the issue. The Predatory Paradox: Ethics, Politics, an Practices in Contemporary Scholarly Publishing (2023) by Amy Koerber et al opens up the discussion to wider implications for scholarly communications as a whole in terms of open science, research quality and integrity issues. Most pertinently, it also offers detailed support for both students, teachers and researchers alike into how to navigate the often confusing, fractured world of academic publishing.

Predatory Publishing and Global Scholarly Communications by Monica Berger

The ‘predatory paradox’ identified by Koerber et al in their book relate to the many conflicts and tensions that arise not just from predatory practices, but also the ‘publish or perish’ culture that has been identified by all the authors so far as one of the main reasons predatory journals sprung up in the first place. In her book Predatory Publishing and Global Scholarly Communications (2024), Monica Berger also takes into account this driver, as well as several other historical factors that help explain predatory journals’ prevalence across multiple subject areas and countries around the world. Like Xia, Berger’s background is in academic libraries, and as such the key role they play on campuses to advise, guide and teach researchers about the integrity of scholarly resources is very much to the fore. Indeed, Berger offers a series of solutions based on pedagogy to try to manage and ultimately negate the impact that predatory journals have, offering at least one way forward for the research community.

Predatory Practices in Scholarly Publishing and Knowledge Sharing: Causes and Implications for Scholarship edited By Pejman Habibie and Ismaeil Fazel

The books reviewed so far have taken a broadly academic approach to the issue of predatory publishing, and this certainly applies to the final book, Predatory Practices in Scholarly Publishing and Knowledge Sharing (2024). This is a collection of articles edited by Pejman Habibie and Ismaeil Fazel, and is the most scholarly of the books reviewed here, with each article taking an in-depth look at certain facets of not just predatory journals, but conferences and other practices as well. Also unlike the other titles, this book investigates some of the key modus operandi of predatory publishers, such as the use of spam email to solicit submissions, how predatory conferences work and even the language that is used to lure authors in.

Final Remarks

Common among all the books are discussions on how to define predatory publishing. This seems to be a real struggle, and at the heart of it is another paradox, namely that the notion of predatory publishing is very difficult to define in academic terms. When Beall coined the phrase 15 years ago, it captured the essence of something being pirated, nefarious and dangerous. However, to identify precisely what is predatory about a journal or publisher for an academic, who is seeking to identify the 100% truth of something, it is anathema to rely on something so ethereal as this term. So while the mystery and notoriety of predatory journals remain – and certainly while authors still publish their research in them – there are likely to be more books on the subject to follow.