What was the first open access journal? We believe that it is Flora Online that started publishing in January 1987. The journal ceased publication in November 1993, after publishing 29 issues.

When looking back through the scientific record, it often useful to have access to the seminal work. When we write a paper, we always try and note where a particular research area started as we feel that it is important to recognize the pioneers, upon which everything that follows is built upon.

In some of the articles we have written on this site, we have often referred to the open access movement, as this is the movement that predatory publishers and journals rely upon. If you are unsure what open access means, take a look at our article “What is Open Access Publishing? | Is it a good model?“

We assumed that it would be easy to find out which was the first open access journal. In fact, it was not as easy as we thought, but we believe that we have tracked it down.

In this article we let you know how we arrived at that conclusion, but we are more than happy to be corrected, as we would like to be sure that we have the definitive answer to the question posed in this article.

Firstly, we we look at some of the early work on open access, reporting some of the initiatives that were instrumental in the open access movement, with some believing that the open access movement would not be where it is today without these initiatives.

Then we describe how we tracked down, what we believe, to be the first open access journal.

However, this is not a complete history of open access. We’ll save that for another article.

Early References

If you search for either the history of open access publishing or for the first open access journal, there are a number of things that quickly become apparent. These are important milestones in the history of open access, but do not answer the question posed in this article. However, they are worth noting and we briefly discuss them here for completeness.

arXiv

Pronounced archive (the X represents the Greek letter chi), this service was introduced in in August 1991, by Paul Ginsparg. He recognized the need for a central repository for pre-prints of papers, which were then available for others to download. Many see this is one of the key moments in the history of open access, for example see this article on the “History of the Open Access Movement.”

Being 1991, the access methods were initially limited but others were soon added, including FTP in 1991, Gopher in 1992 and the Word Wide Web in 1993. The term e-print was used to describe these articles and that term has remained in use ever since.

ArXiv is still available today. If you take a look at its web site, you can see that it holds getting close to two million articles (we accessed the web site on 25 Oct 2020) and it covers a variety of topics, as can be seen by this quote taken from its web site.

“arXiv is a free distribution service and an open-access archive for 1,782,389 scholarly articles in the fields of physics, mathematics, computer science, quantitative biology, quantitative finance, statistics, electrical engineering and systems science, and economics. Materials on this site are not peer-reviewed by arXiv.“

In our experience, arXiv is used a lot these days for scholars to stake a claim on an idea as they know that to polish a paper, submit it and get the results of peer review can take a lot of time and they would like to have a record of what they were working on.

Putting a paper on arXiv also means that others can cite the paper, which also helps the researcher’s profile and, ultimately, the impact of their research.

One word of caution, when we review papers and see that there are references to arXiv we also note that these papers have not been peer reviewed, so whilst it is okay to cite them now (as part of the peer review process), they should either be replaced with a peer reviewed version in the final, or removed altogether.

SciELO

The aim of SciELO is to help with the scientific communication within developing countries, providing a way for those countries to increase the visibility of their research and make it easier to access their scientific literature.

Originally established in Brazil in 1997, there are now 14 countries in the network (last accessed 25 Oct 2020); these being Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Portugal, South Africa, Spain and Uruguay.

The following is the abstract from:

Packer A. L. (2009) The SciELO Open Access: A Gold Way from the South, Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 39(3), 111-126

“Open access has long emphasized access to scholarly materials. However, open access can also mean access to the means of producing visible and recognized journals. This issue is particularly important in developing and emergent countries. The SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library On-line) project, first started in Brazil and, shortly afterward, in Chile, offers a prime example of how this form of access to publishing was achieved and how open access in the traditional sense was incorporated within it. Open access has allowed more visibility, transparency, and credibility for the SciELO journals that now span over a dozen countries, three continents, and more than 600 titles. Conversely, SciELO incarnates the most successful and impressive example of gold OA, that is, open access based on publishing rather than self-archiving; at the same time, its database acts like an open-access depository.“

This sums up the origins of SciELO, along with its aims and its progress to date. If you want to know more about SciELO, we would recommend that you take a look at this paper.

The First Open Access Journal

As we said in the opening it was not easy to track down the first open access journal and, to be honest, we are still not convinced that we done that. However, below we talk through some of the resources we accessed, along with the conclusion we arrived at.

Open Access Directory: Timeline

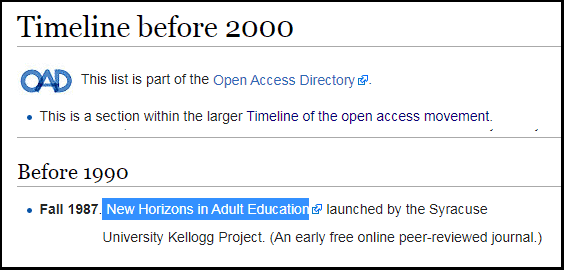

There is a really great resource, called the Open Access Directory, which is a set of lists that covers many areas of open access that you might find useful. Of particular interest was a timeline list, especially the page for pre-2000.

New Horizons in Adult Education

The earliest journal we can see in the Open Access Directory (OAD) timeline is New Horizons in Adult Education. Unfortunately, the link shown on the OAD page no longer works (accessed on 25 Oct 2020). Just for the record, it was trying to access http://www.nova.edu/~aed/newhorizons.html, but that led to a “404” error (i.e page not found).

New Horizons in Adult Education & Human Resource Development

We searched for the New Horizons in Adult Education journal and found a journal published by Wiley (see Figure 2), but with a slightly different name (New Horizons in Adult Education & Human Resource Development). It says that it was first published in Fall 1987, which agrees with the date given in Figure 1.

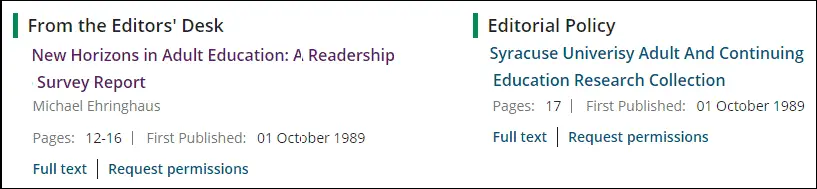

We have also found other evidence that these two journals are the same entity. Much of this evidence is based on the following article we located.

- Hugo, Jane and Linda Newell. (1991) New Horizons in Adult Education: The First Five Years (1987-1991) The Public-Access Computer Systems Review 2(1), 77-90

This article is freely available from https://uh-ir.tdl.org/handle/10657/5149, but we have also made a copy available from this link.

Here is the evidence that leads us to believe that it is the same journal.

- As we said above, both journals started publishing in the the Fall of 1987.

- In the Hugo, 1991 article, it says that the second editor (1989-1990) of New Horizons in Adult Education was Jane Hugo, who was one of the authors of the article that reviewed the first five years (Hugo, 1991). Whilst not being conclusive evidence, it is suggestive that the two journals are the same, or at lest connected through a former editor.

- The first editor (Michael Ehringhaus (1987-1990) is also mentioned in the survey article and we can see this editor appearing in the journal in 1989 (see the left hand side of Figure 3), when writing from the editor’s desk.

- The Hugo, 1991 paper mentions a editorial policy that was published in New Horizons in Adult Education. Specifically it says “The editorial policy guidelines, published in the third issue (Fall 1989) of New Horizons …” Looking at the right hand side of Figure 3, you can see that an editorial policy was published in October 1989, with this entry being taken from Wiley’s web site for New Horizons in Adult Education & Human Resource Development.

We believe that this provides conclusive evidence that the journal New Horizons in Adult Education was started in the Fall of 1987 is the same journal that is now named New Horizons in Adult Education & Human Resource Development.

At some point the original journal was acquired by Wiley and, perhaps at the same time, was renamed New Horizons in Adult Education & Human Resource Development. We could dig even deeper and look at the individual articles and work out when the change took place, which would provide even more evidence.

We did not do this as it would take some time, and we feel that the evidence above is conclusive enough for what we require. Moreover, the articles are now behind a firewall so, although the journal may have started out as open access, this is no longer the case and even those papers that were published back as far as the late 80’s, they are still subject to the reader paying (or having some sort of subscription).

We note that this goes against the spirit of open access where, once something is in the public domain, it should remain there. Perhaps, we are missing something but it does seem perverse that a journal which is a candidate for being labelled as the first open accessed journal now sits behind a paywall.

Learned Publishing

We found a very useful resource:

- Crawford W. (2002) Free Electronic Refereed Journals: Getting Past the Arc of Enthusiasm. Learned Publishing, 15, 117-123. DOI: 10.1087/09531510252848881

The abstract of this article reads:

“Do free electronic refereed journals represent one viable alternative to overpriced commercial journals? This informal study looked at 104 titles listed in the 1995 Directory of Electronic Journals, Newsletters and Academic Discussion Lists (published by the Association of Research Libraries) as being free, journals, and refereed. Taking five years of continuing publication as an initial sign of reasonable longevity (later raised to six years), the record shows reasonable promise. While quite a few early journals succumbed to the ‘arc of enthusiasm’, more than half are still publishing.“

This looked like a good paper to ascertain the first open access journal. Of interest to our discussion is the statement that appears in the body of the paper.

“The Association of Research Libraries’ (ARLs’) Directory of Electronic Journals, Newsletters and Academic Discussion Lists for 1995 includes 104 items that appear to be free, refereed, scholarly electronic journals.“

Crawford goes on to say that some journals started before 1995, were typically distributed by email, or other non-web distribution methods. In the rest of the article, Crawford recounts his experiences in tracking down the journals, as far as he could. Of the 104 journals, 86 were available as free and 49 of those were publishing six years after 1995, so still publishing in 2000.

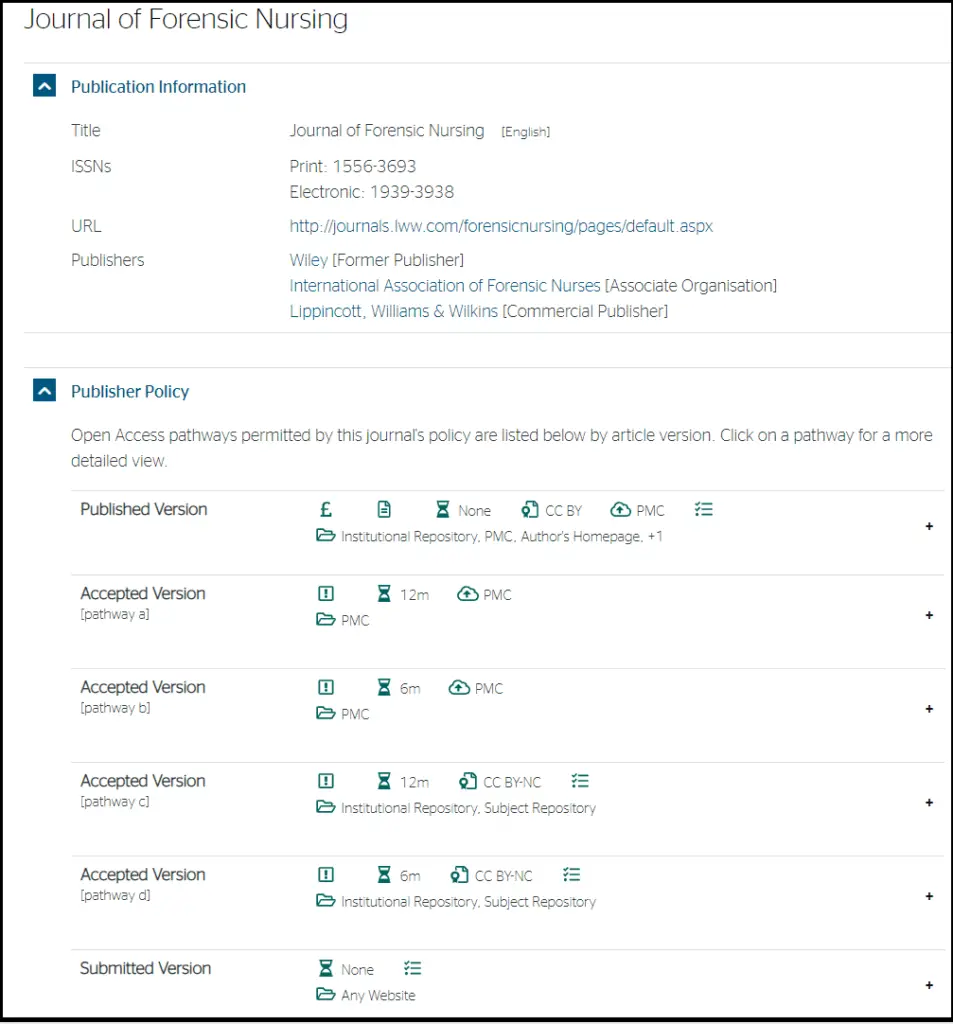

In the context of this article, the most useful part of Crawford’s article is the list of journals that he has been able to track down. This includes when it started publishing.

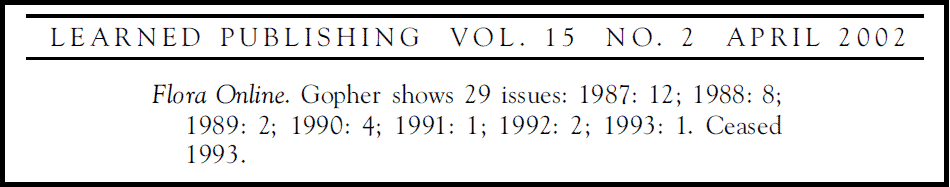

By inspecting this list (and searching by years, gradually going backwards in time), we can only find one journal that was first published in 1987, with none being found for any earlier years (see Figure 4).

Flora Online

From the above investigations/discussions we have reached the conclusion that Flora Online was the first open access journal. We note that New Horizons in Adult Education also appeared in 1987, but this was in the Fall (October), whereas Flora Online first appeared on 12 January 1987.

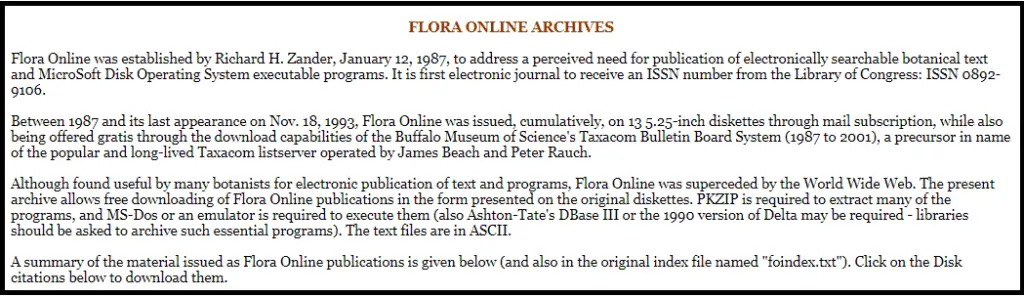

We have managed to track down an archive of the journal, which agrees with the entry by Crawford (Figure 4) that it started in January 1987 and was closed down in 1993.

In case you are interested, here are some key facts about this journal.

- Flora Online was first published on 12 January 1987.

- The last issue was published on 8 November 1993.

- The journal was established by Richard H. Zander.

- The journal was the first online journal to receive an ISSN number from the Library of Congress: ISSN 0892-9106.

- Flora Online published 29 issues, but if you add up the issues shown in Figure 4, it totals 30. Looking at the archive, there seems to be some ambiguity with issue 22, which has an entry for 11 December 1989 and an entry for 5 December 1990.

Conclusion

We have found a journal (Flora Online) that we believe is the first open access journal. It dates back to 12 January 1987. We may be wrong and we would be delighted if somebody would like to correct us.

If we can arrive at an agreement, backed by evidence, of the first open access journal, then we can all cite it, in the knowledge that it is accepted as that by others in the scientific community.