Predatory publishing is the practice of publishers/journals charging fees to publish scientific articles, yet not providing the services that would normally be expected of a scientific journal. This includes not having robust peer review, thus not ensuring the quality and integrity of the papers which will form part of the scientific archive. Moreover, predatory journals may not have an editorial board. Even if they do, the members may not be recognized experts in the discipline being addressed by the journal, they may not make independent decisions and may be influenced by financial considerations.

Predatory publishing is a relatively new phenomena. It was first highlighted by Eysenbach in 2008, in a blog post titled “Black sheep among Open Access Journals and Publishers“. Katharine Sanderson, also raised the issue in her article “Two new journals copy the old“. Jeffrey Beall started writing about predatory publishing in his 2009 article Bentham Open, which we wrote about in one of our other articles.

We believe that the first predatory journal appeared in 2001. Our article “What was the first predatory journal? | Who published it?” explains how we arrived at this conclusion. By comparison, the first journal to introduce peer review, Medical Essays and Observations, was published almost 300 years ago in 1731.

What is the Definition of Predatory Publishing?

There is no universally accepted definition of predatory publishing. There are many definitions out there, but not one which everybody agrees on.

Blog/online definitions

All the proposed definitions have their merits. For example, we cannot disagree with any of these that have appeared in blogs/online articles

“A predatory publisher is an opportunistic publishing venue that exploits the academic need to publish but offers little reward for those using their services.”

What is a predatory publisher?, IOWA State University [link]

“Predatory Journals take advantage of authors by asking them to publish for a fee without providing peer-review or editing services. Because predatory publishers do not follow the proper academic standards for publishing, they usually offer a quick turnaround on publishing a manuscript.“

What is a Predatory Journal?, The University of Texas [link]

“There is no one standard definition of what constitutes a predatory publisher but generally they are those publishers who charge a fee for the publication of material without providing the publication services an author would expect such as peer review and editing.“

Scholarly Communication, The University of Cambridge [link]

Definitions of Predatory Publishing in Peer Reviewed Papers

Some scholars have published peer reviewed papers that have offered a definition of predatory publishing.

As an example, from 2018, What is a predatory journal? A scoping review, opens with:

“There is no standardized definition of what a predatory journal is, nor have the characteristics of these journals been delineated or agreed upon“

From https://dx.doi.org/10.12688%2Ff1000research.15256.2

…. with the article concluding

“Possible objectives could be to develop a consensus definition of a predatory journal.“

From https://dx.doi.org/10.12688%2Ff1000research.15256.2

The article actually undertakes a very good review, but does not provide its own definition.

In Defining predatory journals and responding to the threat they pose: a modified Delphi consensus process, published in 2020, their objective is stated as

“To conduct a Delphi survey informing a consensus definition of predatory journals and publishers“

From https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035561

They invited 115 people to take part in a survey, which resulted in 18 terms that should be included in the definition of predatory journals and publishers. Table 2 in the paper (which is open access, so you are able to easily view it) shows the 18 terms that were agreed as defining a predatory journal/publisher.

A Nature paper from 2019, reported a meeting between between 43 people, from 10 countries representing publishing societies, research funders, researchers, policymakers, academic institutions, libraries and patient partners. After 12 hours of discussion, they arrived at the following definition.

“Predatory journals and publishers are entities that prioritize self-interest at the expense of scholarship and are characterized by false or misleading information, deviation from best editorial and publication practices, a lack of transparency, and/or the use of aggressive and indiscriminate solicitation practices.“

The proposed definition of predatory publishing from Nature 576, 210-212 (2019) (DOI: 10.1038/d41586-019-03759-y)

Our Definition of Predatory Publishing

We have attempted to come up with our own definition, which is shown at the opening of this article, but it is just another, among the many others that have been proposed.

Does it Matter not having an Accepted Definition of Predatory Publishing?

In our view, yes it does.

If we do not have a widely accepted definition of a predatory journal it makes classifying a journal as being predatory difficult. Moreover, we run the risk of arguing about the definition, rather than focusing on trying to stop predatory journals operating. This plays into the hands of the predatory publishers who can simply sit back and watch others argue about what it means to be a predatory journal, rather than having to ensure that they will not be closed down.

When was predatory publishing first highlighted?

As the opening remarks of this article say, the first mention of predatory publishing, although not using the term, was in a 2008 blog post by Gunther Eysenbach. A 2010 article in Nature, by Katharine Sanderson, also highlighted the issue. Following this Jeffrey Beall took up challenge and published a number of articles, and also introduced the term predatory publishing.

In the next two sub-sections, we look at the contribution of Eysenbach and Sanderson. Following this, we focus on Jeffrey Beall’s early contributions.

Gunther Eysenbach’s Blog

The earliest reference that we can find to predatory publishing is a blog post by Gunther Eysenbach on 8 Mar 2008, titled Black sheep among Open Access Journals and Publishers. Gunther does not use the term predatory publishing. This term was introduced by Jeffrey Beall, as we discuss later in this article.

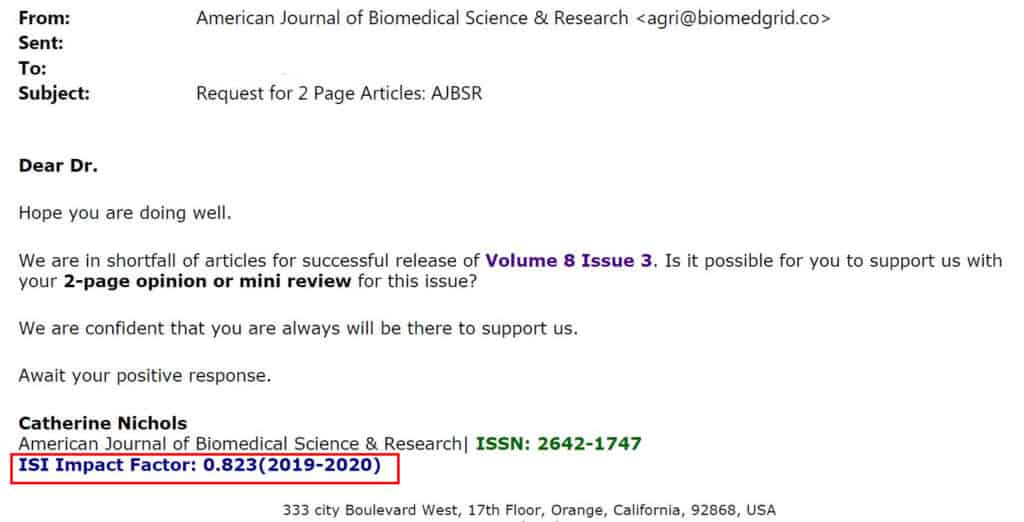

In his blog post Gunther says that he has seen an increase in the number of spam emails he receives from publishers asking him to submit to their open access journal. He highlights one particular journal (Bentham Open) which, over a two month period, sent him 11 emails. The emails were seeking submissions to different journals from their 200+ portfolio. They were keen to recognize his eminence and they pointed out that their institution, or a research grant, would probably pay their modest open access fees.

If you have the time, we would encourage you to read Eysenbach blog post, or at least have a quick glance through it. It was written more than 10 years ago but the concerns raised by Eysenbach are still very much issues today. The only difference seems to be that the problem is now very much worse, with, alas, no sign of getting better.

Katharine Sanderson’s Nature Paper

In January 2010, Katharine Sanderson published a paper in Nature entitled Two new journals copy the old. The papers opens as follows:

“At least two journals recently launched by the same publisher have duplicated papers online that had been published elsewhere.“

Opening sentence from Two new journals copy the old, Nature, 2010

The article focuses on the publisher Scientific Research Publishing, which still operates today. In its journal, the Journal of Modern Physics, it reproduced two papers from the New Journal of Physics (DOI:10.1088/1367-2630/2/1/331 and DOI:10.1088/1367-2630/2/1/323). The Journal of Modern Physics said that this was a mistake due to it posting sample content on the journal’s web pages and the content was removed.

Other notable quotes from Sanderson’s article include:

“The Scientific Research journal Psychology also contains papers that seem to have been published previously, including one in its first issue that was awarded an Ig Nobel Prize in 2000 after being published elsewhere.“

“The home page for the Journal of Biophysical Chemistry contains only the titles and page numbers of four papers in the first issue. Identical paper titles appear in the Journal of Bioscience, published by Springer India, from 2000.“

We should note that Sanderson’s paper was published in 2010 and we are not saying that Scientific Research Publishing is operating these practices today. Indeed, we take no view whether they are a predatory publisher or not. To ascertain that, would require further investigation, which is not the purpose of this article.

Beall’s First Papers

Jeffrey Beall was an academic librarian at the University of Colorado who was instrumental in highlighting the issues of predatory publishing.

Four of Beall’s early papers, which addressed predatory publishing, were published in The Charleston Advisor. Each of these papers highlighted, and analysed, a number of publishers. Of the 18 publishers analysed, all but one was categorized as predatory.

Beall’s first paper that discussed predatory publishing highlighted one particular publisher, Bentham Open, which was also one of the publishers mentioned in Eysenbach’s blog.

We have discussed Beall’s first paper in another of our articles.

In his second article, which appeared in April 2010, it was the first time that Beall used the term “predatory” in a scientific article.

This second article analysed nine publishers:

- Academic Journals

- Academic Journals, Inc

- ANSINetswork

- Dove Press

- Insight Knowledge

- Knowledgia Review

- Libertas Academia

- Science Publications

- Scientific Journals International

Beall published another paper in 2010, which reported another three predatory publishers:

- Medwell

- International Research Journals

- OMICS Publishing Group

In 2012, Beall’s fourth paper looked at another five publishers:

- Academy Publish

- AOSIS Open Journals

- BioInfo

- Science Domain International

- Scientific Research Publishing

These four articles, all published in The Charleston Advisor, analyzed 18 publishers,which published 1,328 journals. Beall categorized them all as being predatory publishers, with the exception of AOSIS Open Journals.

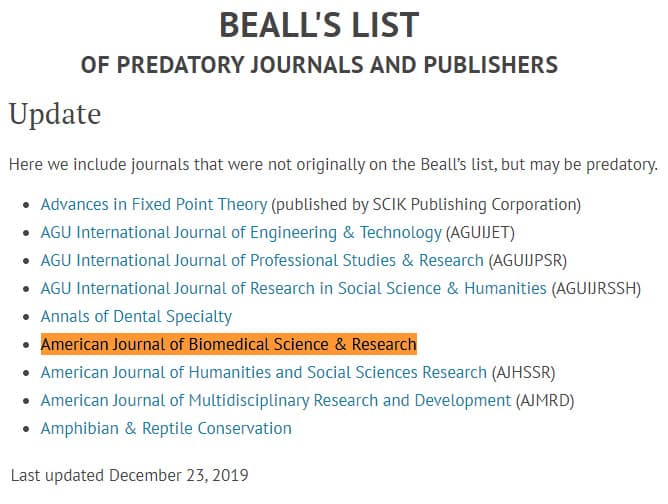

Beall’s List of Predatory Publishers and Journals

You cannot talk about predatory publishing without mentioning Beall’s List. Indeed, it is arguable that without Beall’s List, along with the papers that Jeffrey Beall wrote on this topic, that predatory publishing would have received the attention that it has.

Beall’s List is such an intrinsic part of predatory publishing, we have devoted a separate article to it. This article tells you when the list was set up, when it was taken of line, why it was taken down and some of the criticisms leveled at the list.

Is the number of predatory journals increasing?

One of the challenges in trying to monitor predatory journals is that there is no universally agreed way to categorize a predatory journal. As such, there is no robust way to monitor if they are on the increase or decline, although we should be able to look at general trends and draw some conclusions.

In the next two sub-sections, we consider Beall’s List and papers from the scientific archive, which have both provided a viewpoint as to how many predatory journals there are.

Beall’s List

The challenge of categorizing journals is illustrated in Beall’s List where the decision whether a journal was predatory was made by one person and there was sometimes disagreement whether a journal should be on the list or not, often with representation from the journal itself. It is arguably, for this reason, that the journal was taken offline, largely due to the objection from Frontiers (read more here).

In our article which looked at Beall’s list, we note that the number of predatory publishers on the list in 2011 was 18, rising to 1,115 in 2017. The number of predatory standalone journals was 126 in 2013, rising to 1,294 in 2017. The graphs in our article show the steep rise in the number of journals that Beall classified as predatory.

We may argue about some of the journals on Beall’s List, but we believe that the evidence provided by Beall shows that the number of predatory journals and publishers rose between 2011 and 2017. Either that or they were there all the time and Beall only discovered them over the years he was maintaining Beall’s List. If we wanted a definitive answer to this question, we would need to look at when the journals published their first issue. We do not believe that this work has been done or, at least, it has not been reported in one place. It would actually be an interesting study.

Scientific Archive

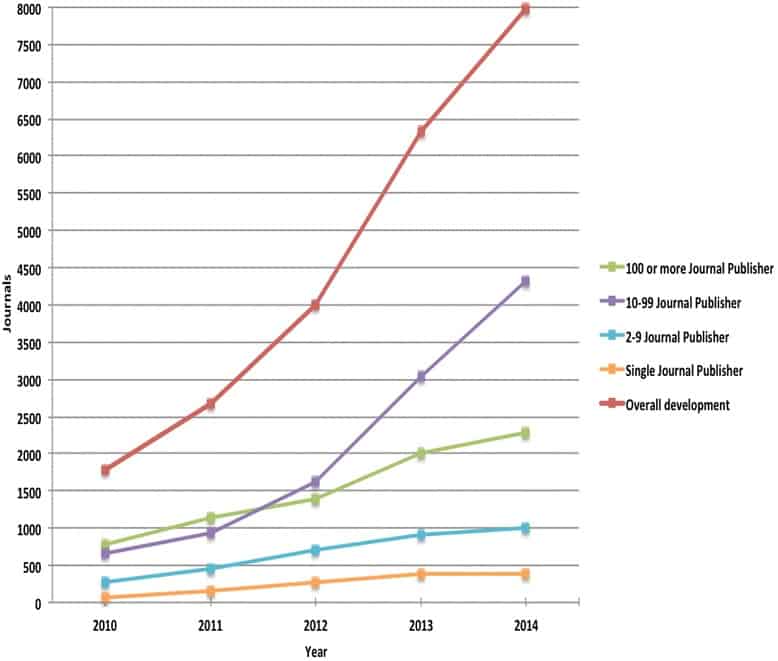

The paper that is most often cited, to show the rise in the number of predatory journals is “‘Predatory’ open access: a longitudinal study of article volumes and market characteristics“. The authors say:

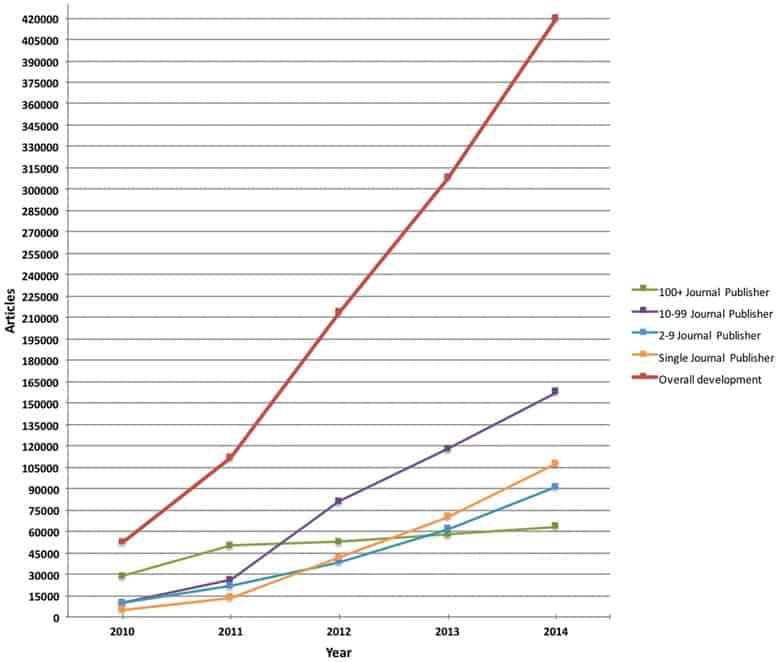

“Over the studied period, predatory journals have rapidly increased their publication volumes from 53,000 in 2010 to an estimated 420,000 articles in 2014, published by around 8,000 active journals.“

Figure 3 (taken from the article, under CC BY 4.0) shows the increase in the number of predatory journals, with a rise from under 2,000 journals in 2010 to around 8,000 in 2014. The figure also shows the statistics for publishers who publish a different numbers of journals.

Figure 4 (also taken from the same article, under CC BY 4.0) shows the number of predatory articles that were published between 2010 and 2014, showing a rise from about 53,000 articles in 2010 to about 420,000 articles in 2014. Similar to Figure 3, there are also statistics breaking down the figures based on the number of journals a publisher produces.

Why should you care?

If we accept that predatory journals exist, should we care? Why not just ignore them, and hope they go away? It may not be as easy as that.

Here are four reasons why you should care about predatory journals. We have provided a link to some of our other articles, where we believe that this might be useful.

- Damaging the integrity of the scientific archive: If papers that have not been properly peer reviewed are allowed to get into the scientific archive, then it damages the archive in a number of ways, including:

- The results that are being claimed may not be correct.

- The reported results may not be reproducible.

- The findings in the paper may simply be a work of fiction.

- Others may rely on the results and try to develop them further, which is likely to be futile.

- The scientific archive is a trusted resource. If that trust is broken it could bring the entire archive into question.

- The results from the predatory papers may be used to advertise products to the general public. Indeed, to do this, might be the motivation to publish the paper.

… further reading

- Cost to the tax payer: A lot of research is funded by the tax payer, with the funds being distributed by research funding agencies. If some of that money is used to pay the article processing charges to predatory publishers/journals this is a waste of tax payers money which could be used for other research and/or other services that would benefit the general public.

- Damage to your CV: If your CV is littered with papers published in predatory journals, or even if you have only published one or two, this will have a negative effect on your CV. It may get you another job, it may get you promotion but ultimately your CV will be judged for what it is.

… further reading - Lack of Impact: Papers which you publish in predatory journals are unlikely to get the attention that you might get if you published your paper in a non-predatory journal. This is due to many reasons, including:

- The journals are not so well known, so are unlikely to be the “go to” place for those looking for a paper to cite.

- Predatory journals tend to be very broad, so it may be difficult to find a paper in your discipline, among the many others which have nothing to do with your discipline.

- Even if your paper is well written and is underpinned by robust research, it is likely to be among papers which are not of the same quality. As a result, your paper could be ignored in the belief that the journal doe snot publish high quality papers that are worth citing.

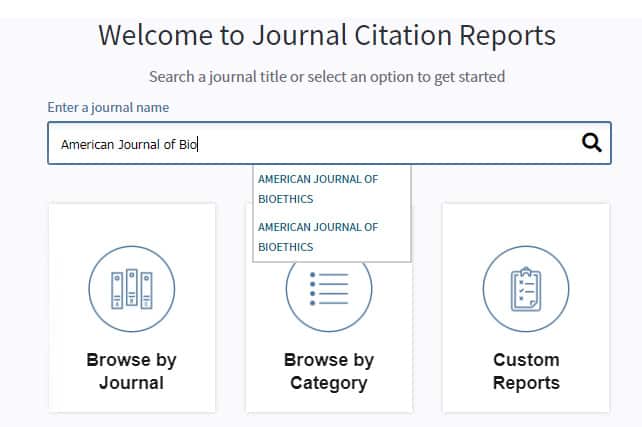

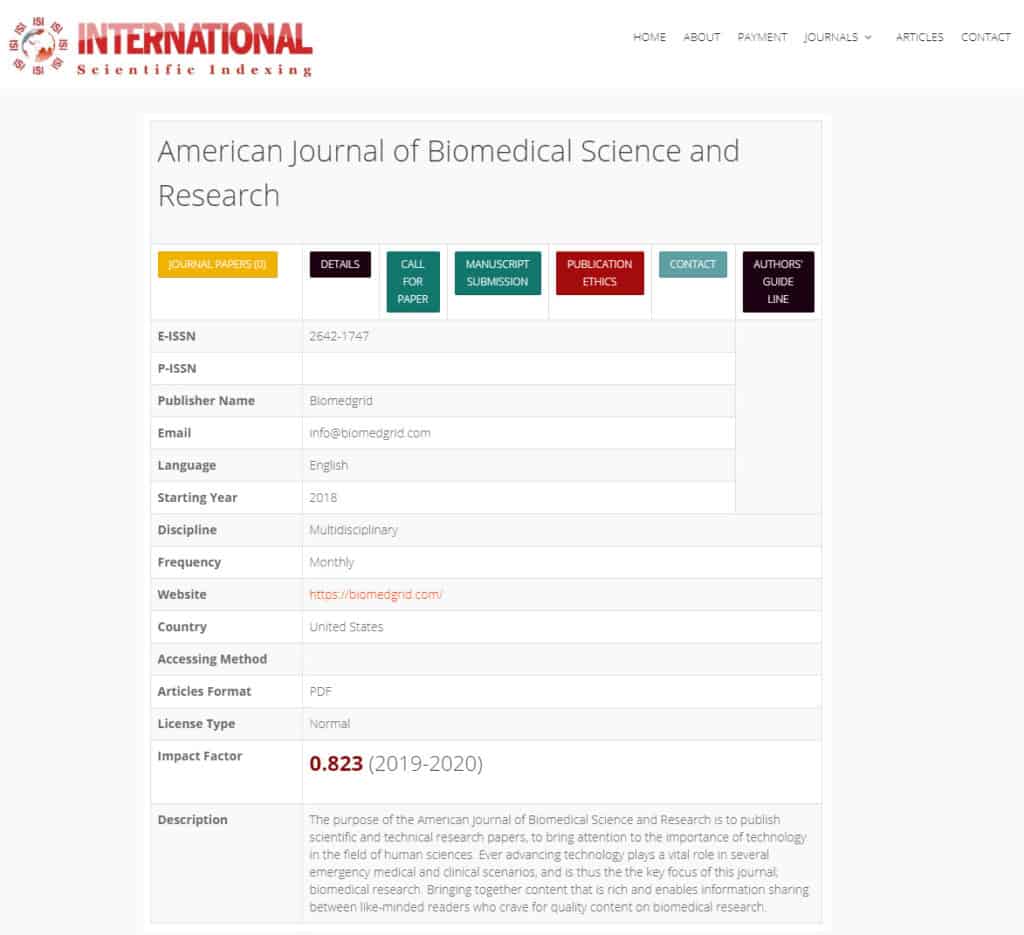

- Predatory journals are unlikely to be indexed by the major bibliographic databases (such as Web of Science and Scopus), so may not be on the radar of researchers who rely on those databases as their main source of references.

… further reading

Conclusion

Predatory publishers exploit the open access model of publishing by charging a fee to publish scientific articles. However, they lack the services that you would normally expect from a scientific publisher, most importantly a robust peer review process. This results in papers being entered into the scientific archive which have not been peer reviewed to the standards that we would normally expect.

Predatory publishing has been around since around 2000, but only started to attract the attention of critics in about 2008. Since then, there have been many studies, with only a small sample being mentioned in this article, but our other blog articles will reference more studies if you are interested.

Both Beall’s List and peer reviewed papers have shown the significant rise in the number of predatory publishers and journals in recent years. Unfortunately, unless we are missing something, there is not a recent study so it is hard to gauge if this increase is continuing. It would certainly be useful if somebody produced an updated study.

Part of the problem is that there is no widely accepted definition of predatory publishers. Most of the definitions that are provided are quite similar and the scientific community would benefit from converging to one definition, so that the community can focus on tackling the problem of predatory journals, rather than trying to come up with a definition which classifies what a predatory journal is.

Predatory publishing should be of concern to all researchers that would like to be able to rely on the scientific archive. Researchers with any integrity should be opposed to predatory journals and publishers and should do what they can to eliminate them from the research community.

Acknowledgements

- Gaping Crocodile image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crocodile_Gaping.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Journal image: http://ppublishing.org/about/, (search for ESR_11-12(74-75) in Google images), CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

The above two images were combined to create the header image that is used for this article.