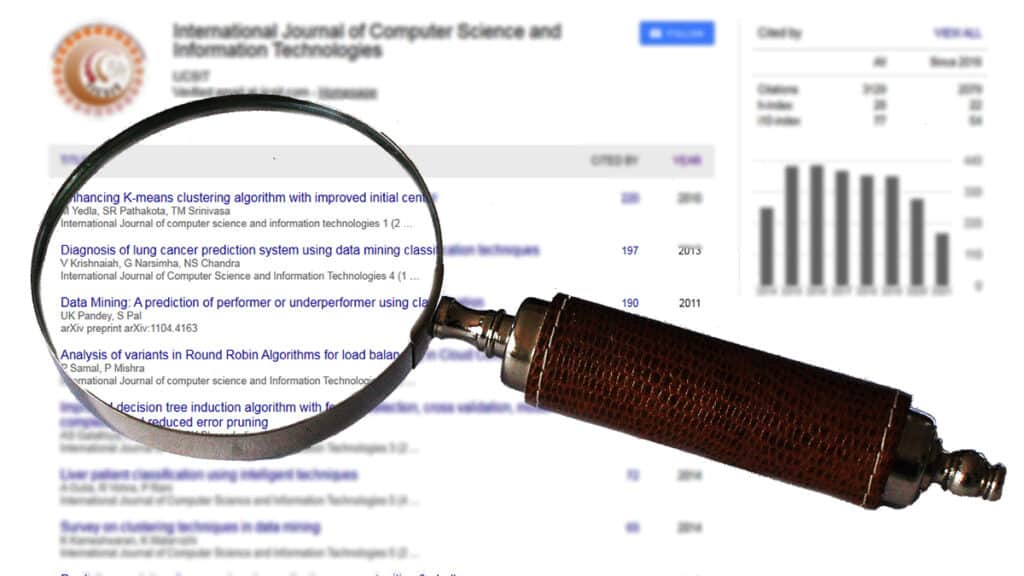

Verifying a Google Scholar impact factor?

For any impact factor, you should be able to verify (i.e. reproduce) it. With Google Scholar, this is possible but can be time consuming and it also requires a certain level of knowledge that many may not posses.