As soon as you start looking at predatory publishing, either as an academic pursuit or because, as a scholar, you do not want to be duped, you will quickly become aware of Beall’s List. This list was established in an attempt to alert scholars to the journals they should avoid as they followed the open access model but were more interested in attracting article processing charges than carry our robust peer review and provide other services that would be expected from a scientific publisher. You might want to look at another two articles we wrote that gives our view as to why predatory publishing is evil and how publishing in predatory journals can harm your CV.

Beall’s List is a list of predatory journals and publishers. It was established by Jeffery Beall in 2010. It became the “go to” place for anybody who wished to know whether the journal they were planning to submit to was predatory or not. Beall took the list offline, without notice, in 2017, after coming under pressure from publishers, his peers and his own institution. Although the list was criticized, many saw it as a valuable resource and were sorry to see it go.

In this article we look at when the list was started, why it was closed down and some of the criticisms that Beall’s List attracted.

Setting up the list

Beall started a blog in 2010 which listed journals and publishers that he believed were predatory in nature. He had previous written about predatory publishing, with his first paper being published in 2009. We believe that this paper is a seminal paper in this area and we have dedicated another article just to this one paper.

This first blog contained fewer than 20 publishers and was largely ignored. Beall reports his experiences about these early days, in his paper Medical Publishing Triage – Chronicling Predatory Open Access Publishers, where he says

“Later, in 2010, I published my first list, which contained fewer than 20 publishers. The list, published on a former blog of mine, was largely ignored.“

A quote from Beall, making comment about his predatory publishing blog

In 2012, Beall moved his blog to a WordPress platform, calling it Scholarly Open Access, but it became known as Beall’s List, and this term is invariably how it is referred to, both then and now.

This second iteration of the blog contained a watchlist. This, we assume, was designed to be a list where journals/publishers were not yet categorized as predatory, but Beall would monitor them and, perhaps, move them to the main list at a later date. However, inclusion on the watchlist was perceived as the same as being as on the main list and, in effect, there was only one list and being on the watchlist was considered as a black mark against the journal/publisher, even if the journal had not been fully investigated by Beall.

Beall’s List was available between 2010 and 2017. On 15 January 2017, the list was suddenly, without warning, taken down by Beall (we discuss the reasons for this below).

At the time the list was taken down, it contained 1,163 journals and 1,311 stand-alone journals. These figures are from https://beallslist.net/, which is an archived version of Beall’s List.

Archive of Beall’s List

When Beall took his list offline, it was archived in a number of forms. Beallslist.net has already been mentioned above.

The location of the original list appears to have been taken over by Stef Brezgov, who has archived part of Beall’s blog posts at https://scholarlyoa.com/publishers/.

If you want to see reports from individual years, you can access the following links; 2015, 2016 and 2017.

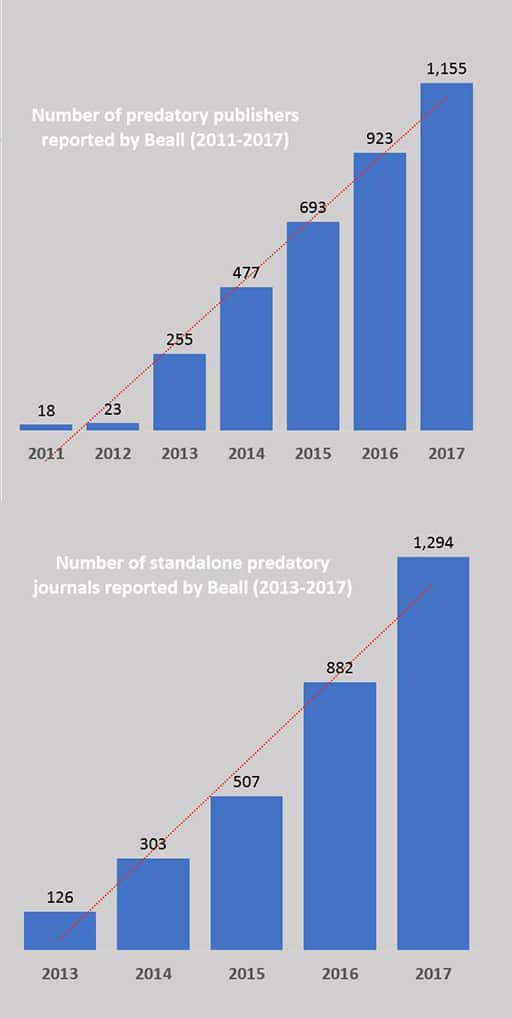

If you look at the 2017 link, you will see the data shown in the table below. We also show the data in graphical form, as it is enables us to include a trend line and it is also slightly easier to see the how the data changes on a graph, rather than trying to interpret the table.

| Year | Number of Publishers | Number of standalone journals |

| 2011 | 18 | Not reported |

| 2012 | 23 | Not reported |

| 2013 | 225 | 126 |

| 2014 | 477 | 303 |

| 2015 | 693 | 507 |

| 2016 | 923 | 882 |

| 2017 | 1,115 | 1,294 |

The data shows how the number of predatory publishers and standalone journals, in Beall’s opinion, grew over the years. For predatory publishers, there were 18 in 2011, growing to to 1,115 in 2017. Standalone journals also saw a dramatic increase from 126 in 2013 to 1,294 in 2017. The trend lines in the two graphs shows how quickly the number of predatory publishers/journals grew. We do not have access to any data since 2017, but we suspect that the number of predatory publishers/journals has further increased.

Closure of Beall’s List

Since starting his blog, many institutions promoted the list to their scholars as a way of identifying predatory journals. Publishers had used various methods to get themselves removed from the list and these gradually became more intense, including writing to Beall himself, writing to senior colleagues at his institution and making accusations about his ethics and his judgement. He was attacked by other academic librarians, some of which were personal in nature.

Beall took his list offline, with no warning, on 15 January 2017. Andrew Silver reported this on 18 January 2017, giving some reasons why the list may have been removed. This includes publishers threatening to sue, the lack of transparency, the fact that Beall is the only person making the decisions and difficulties in getting off the list once on it.

Paul Basken, in a University World News article (22 Sep 2017), gave the following as the “prime suspects” for the list be taken offline.

– His fellow university librarians, whom Beall faults for overpromoting open-access publishing models.

– A well-financed Swiss publisher, angry that Beall had had the temerity to put its journals on his list.

– His own university, perhaps fatigued by complaints from the publisher, the librarians, or others.

– The broader academic community – universities, funders of research, publishers, and fellow researchers, many of whom long understood the value of Beall’s list but did little to help him out.

– Beall himself, who failed to recognise that a bit of online shaming wouldn’t stop many scientists from making common cause with journals that just don’t ask too many questions.

Paul Basken’s “prime suspects” as to why Beall shut down his list

In his 2017 paper (15 June 2017) Beall explained his reasons for removing the blog. He said that he was fearful of losing his job and he was facing intense pressure from his employer.

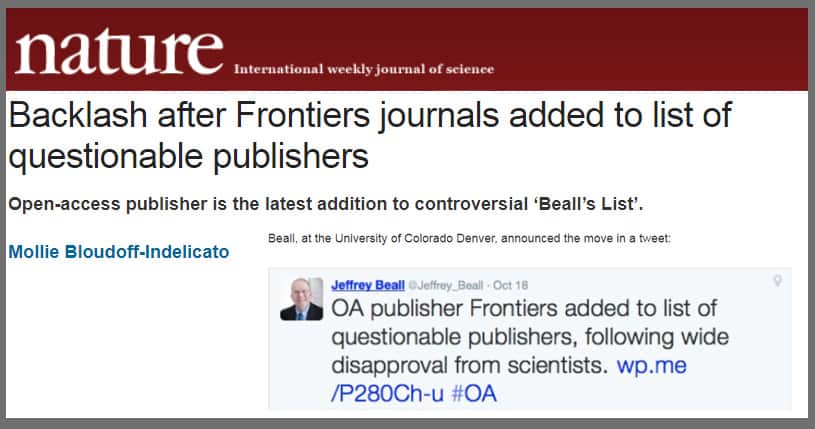

Leonid Schneider, in his 18 Sep 2017 For Better Science article, says that it was the publisher Frontiers that was the prime reason for Beall having to take his list down. Frontiers, at first tried to play nicely but, after Beall refused to remove them from his list, they contacted his employer who opened a misconduct case against him. At the risk of losing his job, Beall removed his list from the internet.

Criticisms of Beall’s list

Beall’s List has its critics. Stephen Kimotho surveyed 30 peer reviewed papers that were critical of Beall. Four major themes emerged:

- Methodological Flaws: Five areas were highlighted from this part of the study

- Dubious basis for enlisting

- Lack of transparency

- Personal opinion and highly subjective

- Lack of criteria for individual entries

- Casting suspicion on start-up publishers.

- Beall’s bias against open access

- Discriminating against developing economies

- Beall’s list being prejudicial against academic freedom

Another criticism that is often leveled at Beall is that he is the only person making the decision whether to include a publisher/journal on his list. When Beall added Frontiers to his list it caused a debate on social media, with one of the Associate Editors of Frontiers remarking “Frontiers being added to Beall’s list reveals the big weakness of Beall’s list: It’s not based on solid data but on Beall’s intuition.” The editor also said “Having a

single influential individual cast doubt on such a huge journal feels very unfair.”

Beall has also been criticized for potentially damaging the reputation of scholars, especially if a journal is added to Beall’s lists after the scholar has published a paper in journal in good faith, but has since been marked as predatory.

The same Frontiers’ Associate Editor said “It could be, the articles people have published in Frontiers are no longer judge based on their own quality, but now seen as less valuable because Frontiers in on Beall’s list.“

If you want to read more about criticisms that have been made against Beall’s approach, you might want to take a look at the following papers.

- The storm around Beall’s List: a review of issues raised by Beall’s critics over his criteria of identifying predatory journals and publishers

- Jeffrey Beall’s “predatory” lists must not be used: they are biased, flawed, opaque and inaccurate

- Ethics and Access 1: The Sad Case of Jeffrey Beall

- Investigating journals: The dark side of publishing

Conclusion

Beall’s List has become legendary in the field of predatory publishing. Whether you agree with the list or not, you cannot ignore it.

There are issues with Beall’s List. One person made the decision whether a journal/publisher was included, the criteria for being on the list were not transparent and publishers/journal had no formal way to appeal against being on the list.

Yet many people relied on the list as the go to place to decide if they should submit a paper to the journal they had in mind. Perhaps it was not perfect, but given the rise in the number of predatory journals and the practices that they used, it was good to have something that scholars could refer to. If it were not for Beall’s List, there would have been no checks and balances at all on predatory publishers/journals.

Since the closure of the list, nothing has really taken its place, which leaves a gaping hole which the list used to occupy. There is plenty of advice on how to identify a predatory journal and even we have written articles which offer advice; how to analyse a journal and three quick ways to spot a predatory journal.

Services such a Cabells exist which, at the time of writing, say they index over 11,000 journals across 18 disciplines. Cabell’s is a paid for service so, unlike Beall’s List you need to have a subscription before you can access information about a specific publisher or journal.

We have no issue with commercial services such as Cabells, who provide a valuable service for those that can afford it. However, it would be useful to have a free service, as Beall’s List was, so that scholars who do not have access to a subscription service can still get information about a given journal. Perhaps that information may not be as rich as Cabells, but providing data so that an informed decision can be made might be useful.